Six types of greenwashing you are likely to come across and what this could mean for your investments

Greenwashing is a phenomenon that has been around for a while, with companies facing scrutiny over what they publish. The term is used to describe the act of making false or exaggerated claims about the environmental benefits of a service or product. As the finance industry seeks to address the growing need for sustainable investment options, it is clear that some companies are not being entirely truthful about their environmental practices and are struggling to find a clear path in the maze of ESG. The European Union (EU) has proposed a new criteria against misleading environmental claims in an attempt to curb greenwashing on environmental labelling and accelerate the green transition in a more transparent way. According to a 2020 study by the European Commission, 53.3% of 150 examined environmental claims in the EU were considered “vague, misleading or false”. The new criteria proposed means that companies violating the new rule will risk hefty fines and potential removal from the market.

When it comes to ESG metrics, firms have a plethora of frameworks to follow which opens the door to many ambiguous interpretations. Although this is a sign that the ESG agenda is growing, it also puts significant and increasing pressure on firms to select the right one that will not portray the company as “cherry picking”. There seems to be no difference in harm with firms either prioritising as many metrics as possible or choosing a select few to ensure data is accurate as both paths ultimately can be portrayed as greenwashing since each strategy is acting on the advantage of the firm.

What are the key issues?

One of the main issues with greenwashing is the lack of clear regulations and standards used for investment decision making. Unaudited data, green claims with no governing body and no specific regulatory guidelines has fostered an environment of misleading information. Companies continue to race to publicise their sustainability credentials, yet our interpretations of “green” or ESG-branded investment funds are often inaccurate despite the willingness of corporates to make a difference.

Another issue that is circulating is the lack of transparency and without clear guidelines companies will continue to generate false, incorrect, incomplete or just non-verified claims that make it difficult for investors to know if their investments are genuinely sustainable. For example, companies may label their funds green, even if the funds are not entirely used for sustainable projects, or companies may be overly cautious and downgrade their funds so that they comply with stricter regulations under the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) so to avoid scrutiny associated with Article 8 or 9. The current integrity of frameworks used to measure sustainability is a concern to companies, especially since highly regarded initiative like the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) have faced complaints about its governance. This ultimately raises the question of who is exactly responsible for greenwashing, intentional or unintentional as it may be.

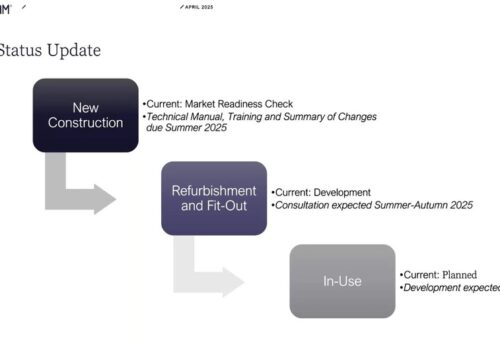

A recent report (J. Willis, The Greenwashing Hydra, Planet Tracker, 2023) has identified at least six types of greenwashing that corporates could be responsible for, stating that a “greenwashing hydra” has emerged when analysing green claims from corporates. It is therefore important to conceptualise greenwashing appropriately and accurately. By identifying the various iterations that greenwashing can fall under, it builds awareness around the need for due diligence when making environmentally led decisions.

What are the types to look out for?

| Types of Greenwashing | Definition |

| Green crowding | Built on the belief that you can hide in a crowd to avoid discovery, relying on safety in numbers. If sustainability policies are being developed, it is likely that the group will move at the speed of the slowest. |

| Green lighting | Occurs when company communications spotlight a particularly green feature of its operations or products, however small, in order to draw attention away from environmentally damaging activities being conducted elsewhere. |

| Green shifting | When companies imply that the consumer is at fault and shift the blame on to them. |

| Green rinsing | Refers to a company regularly changing its ESG targets before they are achieved. |

| Green hushing | Refers to corporate management teams under-reporting or hiding their sustainability credentials to evade investor scrutiny. |

| Green labelling | A practice where marketers call something green or sustainable, but closer examination reveals this to be misleading. |

The EU released its Taxonomy Regulation which aims to create a standardised classification system for sustainable investments and the SFDR which requires financial firms to disclose the environmental impact of their investments. The aim is to increase transparency and provide accurate information for funds to label their portfolios correctly and for investors to make better informed decisions about their investments. Upon reflection, it is great to see companies setting SBTi targets and disclosing information to align with Article 8 and 9, perhaps it is a sign of climate change risk management becoming mainstream, however greenwashing is sill such a central issue and will do more harm than good in both the short and long term. The different types of greenwashing identified highlights the reality of the challenges within disclosing sustainable investments, and the need for technical expertise to ensure due diligence is done correctly. Instead of attacking firms for green washing, we should be educating them on the different types to help contribute to better decision making and education on the issue. This is where value is created and where we can make a meaningful impact. Once firms have tackled these issues, then can we start to sit down and create meaningful paths for the Social (S) and Governance (G) pillars of ESG.

References: